|

Vertical Divider

|

Natural populations are increasingly fragmented as human use of the landscape changes. As populations decline in size and connectivity, they become vulnerable to inbreeding, stochastic effects such as genetic drift, and novel challenges like introduced pathogens and changing environmental conditions. However, less well connected populations may also be more sheltered from infectious diseases. |

Prairie dog populations are threatened by the compounded effects of habitat fragmentation and sylvatic plague, caused by the non-native bacterium Yersinia pestis. Plague is highly virulent to prairie dogs, and epizootics eliminate entire colonies. As a result, populations may undergo severe bottlenecks when extirpated colonies are repopulated by few individuals in nearby colonies. Conversely, if recolonization occurs from multiple source populations, genetic diversity may be maintained.

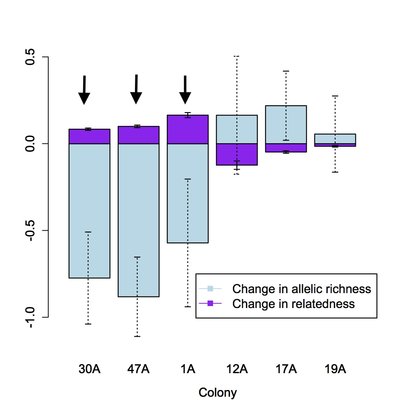

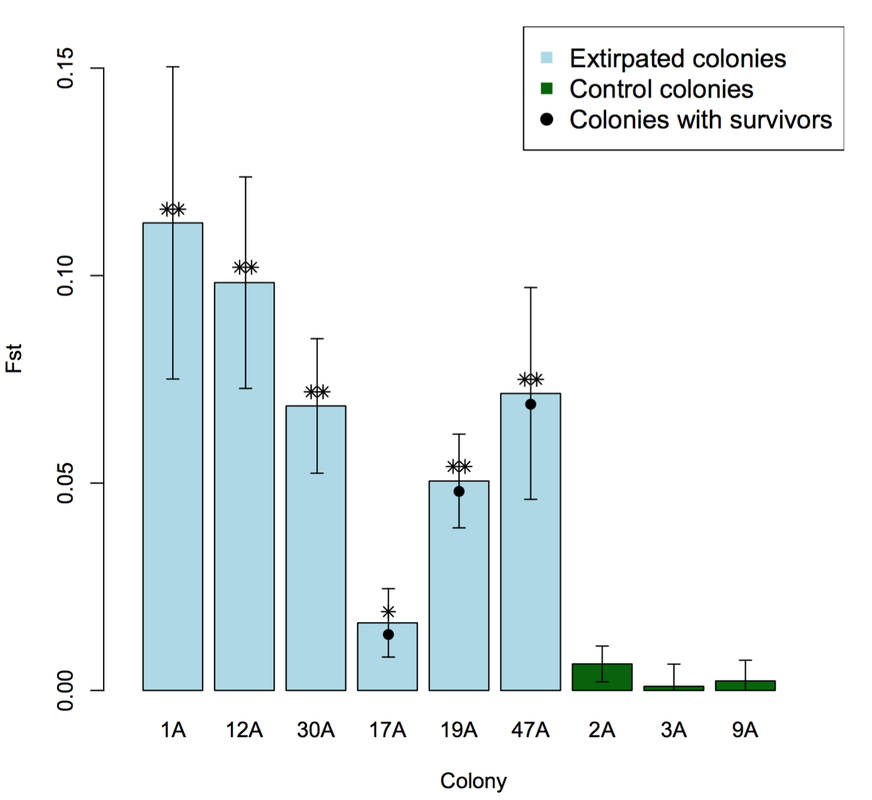

We found that some black-tailed prairie dog colonies were able to regain genetic diversity during the recolonization process, provided there was a sufficient number of source populations for immigrants. In contrast, other colonies--those with few source populations--suffered from a loss of genetic diversity (figure, below left). The outcome seems to depend partially on the degree of urbanization surrounding prairie dog colonies: populations in heavily urbanized areas experience fewer immigrants from fewer source colonies than populations in more natural landscapes. In all cases, the founders of extirpated colonies were genetically different from the individuals present before plague (figure, below right).

We found that some black-tailed prairie dog colonies were able to regain genetic diversity during the recolonization process, provided there was a sufficient number of source populations for immigrants. In contrast, other colonies--those with few source populations--suffered from a loss of genetic diversity (figure, below left). The outcome seems to depend partially on the degree of urbanization surrounding prairie dog colonies: populations in heavily urbanized areas experience fewer immigrants from fewer source colonies than populations in more natural landscapes. In all cases, the founders of extirpated colonies were genetically different from the individuals present before plague (figure, below right).

Vertical Divider

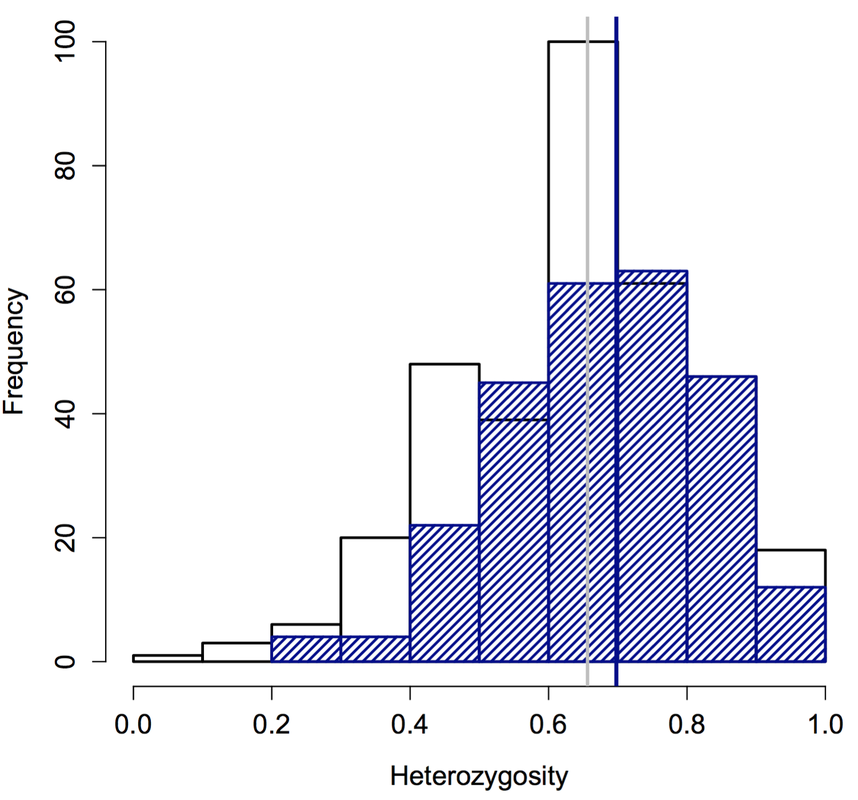

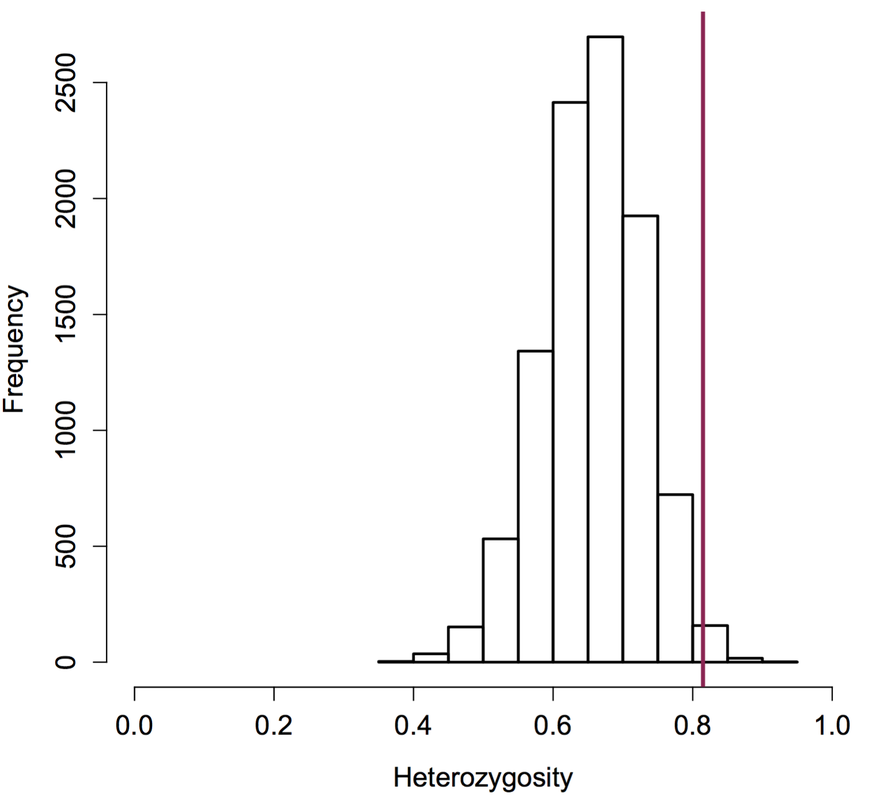

Plague extinctions and recolonization also influence genetic diversity at the scale of individual prairie dogs: Prairie dogs in populations that had been recolonized had significantly higher heterozygosity than prairie dogs in those populations before plague (left figure, below). Moreover, heterozygosity of six survivors (vertical bar in right figure, below) was strikingly higher than expected due to chance. This work contributes to our understanding of how animals evolve in response to introduced diseases, especially in anthropogenically altered landscapes. This work was funded primarily by the Boulder County Nature Association, the University of Colorado Natural History Museum, the University of Colorado (CU) and CU’s Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology. You can read the full paper here and find out about my ongoing work--which seeks to explore the genetic underpinnings of resistance and why resistance is not more widespread--here.

Reference: L.C. Sackett, S.K. Collinge, A.P. Martin 2013. Do pathogens reduce genetic diversity of their hosts? Variable effects of sylvatic plague in black-tailed prairie dogs. Molecular Ecology 22: 2441-2555. Download PDF

Collaborators:

Andy Martin, University of Colorado

Ryan Jones, University of Arizona

Sharon Collinge, University of Colorado

Collaborators:

Andy Martin, University of Colorado

Ryan Jones, University of Arizona

Sharon Collinge, University of Colorado